In Conditions

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Parasitic infections are often associated with developing countries or holidays to far-flung locations, but there are some parasites – lice, worms and mites – that commonly infect humans (especially children) here in the UK.

Many people associate parasites with poor hygiene, yet this isn’t always the case. Some parasites are spread by ticks or mosquitoes or may be transmitted from animals to humans.

Parasitic infections don’t always cause symptoms, and many people are affected without knowing it. Some common symptoms of parasitic infections – such as itching or diarrhoea – may be attributed to other conditions.

However, a parasitic infection can sometimes cause severe symptoms and impact someone’s overall health. Understanding parasites is important when advising pharmacy customers about preventing and treating common infestations.

Thread ahead

Threadworm (pinworm) is the most common parasitic worm infestation in the UK and spreads easily. It mainly infects children under 18 (and their household contacts) and people living in institutions.

European estimates have suggested that 20-30 per cent of pre-school and primary-school children will have a threadworm infection at any one time. Other worm infestations, such as tapeworm, roundworm and hookworm, are more commonly caught abroad, especially by travellers to countries with poor sanitation.

Threadworms can cause intense itching around the anus or vagina, particularly at night. However, sometimes they don’t cause any symptoms.

Instead, the infestation is diagnosed when the tiny thread-like worms are seen on the skin or in the stools. The worms usually come out at night while the person is sleeping. Threadworm eggs aren’t visible to the naked eye.

Transmission occurs when those infected scratch their anal area and then pass the eggs on to whatever they touch, such as surfaces, toys, bedding, clothing and food.

Occasionally, the eggs are inhaled or swallowed in dust (such as after shaking out contaminated bedding). Adult threadworms survive for about six weeks, but reinfection is common, caused by swallowing fresh eggs.

Untreated threadworms can cause secondary bacterial infections, a lack of sleep, irritability, bedwetting, weight loss and a loss of appetite.

Many parents seek over-the-counter (OTC) treatment and advice from a pharmacy, rather than visiting their GP. The treatment usually involves a single dose of mebendazole (a chewable tablet or syrup to swallow).

The dose may need to be repeated after two weeks if the infection persists.

All household contacts aged over two years should be treated, if possible, even if they don’t have any symptoms. Mebendazole isn’t licensed for threadworm in children under two years, so parents will need to discuss treatment with their GP.

Children under six months, and pregnant or breastfeeding women, should be treated with only hygiene measures for six weeks. Hygiene measures include regular and thorough handwashing, keeping fingernails short, showering daily, changing bed linen and nightwear daily, washing clothes on a hot cycle, and regular and thorough dusting and vacuuming, especially the bathroom and toilet.

Head scratching

Head lice are very common in young children and their families. These tiny grey-brown insects cling to human hairs and live close to the scalp.

They are spread mainly by close hair-to-hair contact, but can occasionally spread via bedding, brushes, combs and hats. Head lice aren’t caused by poor hygiene or having dirty hair.

Although head lice can cause itching, many people with head lice don’t have any symptoms. The only way to confirm an infection is to find a live louse – usually with a special fine-toothed nit detection comb, as it’s difficult to see the lice in the hair. Nits (empty eggshells) remain stuck to the hairs when the lice hatch and aren’t a sign of an active infection.

A survey commissioned by Vosene Kids haircare has found that 41 per cent of UK parents said their children have had head lice, and almost a quarter of parents revealed that they have caught head lice from their child.

“The most alarming fact is that the majority of parents (68 per cent) have – or would – keep a head lice outbreak in their household a secret,” says Dr Chris George, GP and Vosene Kids spokesperson.

“Secrecy around reporting infestations could lead to a delay in accessing treatment and allow increased time for transmission of head lice.”

Head lice should be treated as soon as a live louse is found. This means also treating everyone in the household and anyone who has been in close contact with the infected person, all on the same day.

Lice and nits may be removed by wet combing, although many parents find this treatment too time-consuming to maintain.

Wet combing involves using a special plastic, fine-toothed comb to comb through the hair twice in each session – this can take 10 minutes for short hair, and 20-30 minutes for long, curly or frizzy hair.

It helps to apply plenty of conditioner first to make the combing easier. Wet combing needs to be done every four days for two weeks – on days one, five, nine and 13 – and then again on day 17 to confirm there are no live lice.

“Wet combing only works if it’s a consistent technique,” says Ian Burgess, director of the Medical Entomology Centre in Cambridge.

“It needs to be in the right hands, using it on the right people. Wet combing is much easier on shorter and finer hair, and many children won’t sit still for long enough.”

If wet combing hasn’t worked or isn’t suitable, parents can use a medicated lotion or spray instead. The first-line treatment is a physically-acting product containing dimeticone or cyclomethicone.

Lotions and liquids are more effective than shampoos but still need to be left in contact with the hair for eight to 12 hours. Medicated insecticides such as malathion are an alternative, but resistance is a growing problem.

Head lice are even developing resistance to the physically-acting products.

“Many people don’t manage to treat the eggs adequately,” says Ian.

“Even products that during testing were shown to be 100 per cent effective at killing both lice and eggs are less effective than they used to be, after years of use. It’s important that pharmacists check the clinical evidence and that products are MDR compliant.”

In general, a course of treatment for head lice should involve two applications of the product seven days apart to kill lice emerging from any eggs that survive the first application.

Benzyl benzoate is also licensed to treat head lice but it’s less effective than malathion and isn’t recommended for children. There’s no evidence that head lice repellents, electric head lice combs, or plant oils, such as tea tree oil and eucalyptus oil, are effective.

“The most alarming fact is that the majority of parents have – or would – keep a head lice outbreak in their household a secret”

To limit the spread of a parasitic infection, ensure children develop a good habit of washing their hands from a young age.

It mite be an issue…

Scabies isn’t usually a serious infection, but it should be treated as soon as possible to ease the symptoms, reduce the risk of complications and prevent further transmission. The tiny Sarcoptes scabiei mites burrow into the outer layer of the skin.

This causes intense itching (especially at night), small red bumps and blisters, triggered by an immune reaction to the mites and their saliva, eggs and faeces. Sometimes it’s also possible to see s-shaped mite burrows (like wavy lines) in the skin.

Scabies spreads easily through skin-to-skin contact, such as holding hands (more than just a handshake), sleeping in the same bed or through sexual intercourse.

Outbreaks are most common in settings where people live close together.

“Scabies infections are particularly common in the confined elderly, boarding schools and prisons, but the high-risk groups are the under-20s, especially teenagers and primary school children,” says Ian. “And this is often causing the increased transmission to care homes.”

If scabies remains untreated, it can lead to secondary bacterial infections and difficult-to-treat crusted scabies, when a large number of mites are present.

This is more common in people with a weakened immune system or taking immunosuppressant medicines, such as corticosteroids.

In October 2024, the Royal College of GPs highlighted a spike in scabies cases, especially in the north of England and on university campuses.

“The treatment for scabies is a topical cream or lotion,” says professor Kamila Hawthorne, chair of the Royal College of GPs Council.

“The most commonly used are permethrin cream and malathion lotion – these can be purchased in pharmacies, or by prescription in general practice. All patients with the condition should wash their bedding and clothes on a high temperature and avoid physical contact with others until they have completed the full course of treatment. If symptoms persist following treatment, then a patient should contact their GP.”

The UKHSA recently updated its guidelines for the management of scabies cases and outbreaks in communal residential settings to clarify that people diagnosed with scabies should be treated as soon as possible and shouldn’t wait for wider mass-treatment, see: bit.ly/4fSDV1U.

Oral ivermectin may be prescribed for people with pre-existing eczema or other skin conditions that may lead to hypersensitivity if they use topical treatments.

All abroad!

Cryptosporidiosis and giardiasis are two common parasitic infections of the intestines. These are usually associated with travelling abroad but can also be caught in the UK through contaminated swimming pools, streams, lakes and even public water supplies.

Good hygiene is essential to avoid catching the infections or passing them on to other people.

Over 4,000 cases of cryptosporidiosis are reported annually in the UK. Children between one and five years are most likely to be affected, although anyone can catch it, especially if they work with animals or are changing nappies. Outbreaks are sometimes transmitted during farm visits.

The main symptoms are severe watery diarrhoea, stomach pains or cramps, nausea or vomiting, mild fever, weight loss, and a loss of appetite. These usually start two to 10 days after exposure and last for up to two weeks, although this can be longer, especially in people with weak immune systems.

Giardiasis can be transmitted through contaminated water and direct person-to-person contact (including sexual intercourse). The infection can cause smelly diarrhoea, tummy pain or cramps, wind, bloating and flatulence, and weight loss.

It usually goes away after around a week once it’s treated. It’s possible to have no symptoms but still spread the infection to other people. Giardiasis can be diagnosed through a stool sample and is treated with antibiotics.

With both infections, it’s important to rest and drink plenty of fluids to prevent dehydration from diarrhoea or vomiting. If there are any signs of dehydration, such as urinating less than usual and having dark, strong-smelling urine, oral rehydration sachets should be recommended.

If someone is being treated with giardiasis, they shouldn’t drink alcohol, as this can react with the main prescribed antibiotics.

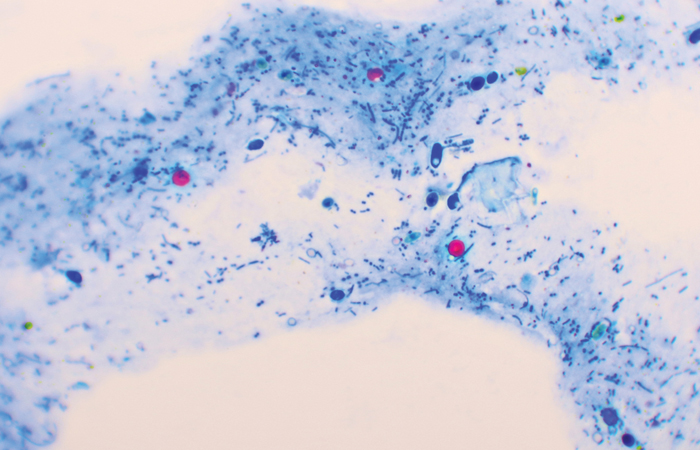

Cryptosporidium is caused by single-celled protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium parvum.

Toxoplasma

Toxoplasmosis is a common parasitic infection caught from infected meat (especially pork or lamb) or, more commonly, infected cat droppings (e.g. in litter trays or soil).

There’s also a small increased risk during the lambing season, as toxoplasmosis infection can pass from sheep to humans. Up to one-third of the human world population is infected with the protozoan parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, and around 350 cases of toxoplasmosis are diagnosed in the UK each year.

Toxoplasmosis is usually harmless and gets better on its own, but it can cause serious problems during pregnancy (such as miscarriage) or in people with a weakened immune system.

The infection doesn’t usually cause any symptoms, which means most people don’t know they’ve had it. When symptoms occur, these are generally flu-like, such as a fever, headache, sore throat, swollen glands and tiredness. More severe symptoms include infected eyes, pneumonia and confusion.

Toxoplasmosis can be diagnosed with a blood test. Most people with toxoplasmosis get better without treatment – but pregnant women, newborn babies and those with severe symptoms are treated with antibiotics and antiparasitic medicines.

Good hygiene, especially when handling cat droppings in litter trays or soil, is particularly important for pregnant women and people who are HIV-positive.

Red flags

Parasitic infections may cause a wide range of symptoms, depending on the specific parasite involved and which part of the body is infested, although sometimes the infections don’t cause any symptoms at all.

It’s important to remain vigilant for symptoms when advising high-risk groups (such as parents of young children) and people who have recently travelled abroad to areas where parasites are particularly common.

Red flag symptoms to look out for include:

- Digestive – abdominal pain, diarrhoea, vomiting and/or bloating

- Skin – persistent itching, a red rash and/or sores

- General – unexplained weight loss, fever, aches and pains and/or dehydration

- Neurological – confusion, headaches and/or sleeping problems.

It is crucial that combing for lice is done consistently until no more eggs or lice remain in the hair.