In In-depth

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Dandruff, cradle cap and other skin concerns are household names, but many people may not be aware that they are caused by the common skin disease, seborrheic dermatitis.

Seborrheic dermatitis does not discriminate based on age – anyone from a newborn baby to an elderly person may suffer from the condition – but symptoms vary from person to person.

The condition ranges from mild dandruff, which dermatologists call pityriasis capitis, to severe red scaly rashes across much of the body that can dramatically undermine quality of life. With flares (exacerbations) interspersing periods of relatively normal-looking skin.

Unfortunately, seborrheic dermatitis in adults is incurable, but there is much to learn about its management.

What to look for

Seborrheic dermatitis is remarkably common. Up to seven in 10 children may develop ‘cradle cap’ (seborrheic dermatitis of a newborn’s scalp) or rashes on their face or nappy area during their first three months. Some estimates suggest that half of adults have dandruff, or full-blown seborrheic dermatitis, but many cases are not severe enough to need treatment by a GP or dermatologist.

“Dermatitis is inflammation in the skin,” explains Dr Emma Ormerod from the British Association of Dermatologists. “Seborrheic dermatitis is an inflammatory condition that in adults can take different forms and affect different body sites.” Typically, seborrheic dermatitis develops on ‘greasy’ areas such as the scalp, forehead, eyebrows and other facial hair, around the nose and behind the ears. Sometimes, seborrheic dermatitis can inflame eye lids and the conjunctiva (blepharoconjunctivitis). Refer patients you think may have blepharoconjunctivitis to their GP.

“Typically, the mildest and more common forms of seborrhoeic dermatitis are on the scalp,” Dr Ormerod says. “Patients note a fine, white, diffuse scaliness with minimal inflammation. More severe forms of seborrheic dermatitis are typically diagnosed when there is more presence on the scalp, as well as on the face and trunk, and these people tend to present with more prominent erythema [red skin] as well as scaling.” In darker skin, seborrheic dermatitis may produce light spots or patches with skin flaking rather than red spots.

In babies

“Nappy rash associated with seborrhoeic dermatitis shows well-defined erythematous papules [red, inflamed lumps or spots] and plaques [patches] with greasy yellow scale in the skin folds,” Dr Ormerod says. Some babies develop a greasy yellow scale on their scalp (cradle cap). Darker skinned babies with cradle cap may show erythema, flaking and light areas (hypopigmentation) on their scalp and skin folds.

“Seborrheic dermatitis is rarely isolated to the nappy area. So, if the rash is just in that area a different diagnosis should be considered,” Dr Ormerod notes. Indeed, other inflammatory skin conditions, such as psoriasis, rosacea, contact dermatitis or tinea versicolor, another skin disease caused by Malassezia yeasts (discussed later), can mimic seborrheic dermatitis. “Knowing when to refer the patient to a GP is important. Other than no improvement with over-the-counter treatment, some of the red flags to consider include a worsening rash, a rash that affects atypical areas or is very extensive, blistering of the skin, or a patient who is unwell and reporting pain,” she says.

“Seborrheic dermatitis is an inflammatory condition that in adults can take different forms”

Grease and yeasts

So, what causes seborrhoeic dermatitis? Sebaceous glands release sebum, a cocktail of lipids (fats), which moisturises and protects skin. Yet, despite its name, excessive sebum production does not usually result in seborrheic dermatitis. The exact cause is not entirely clear. But there are several clues.

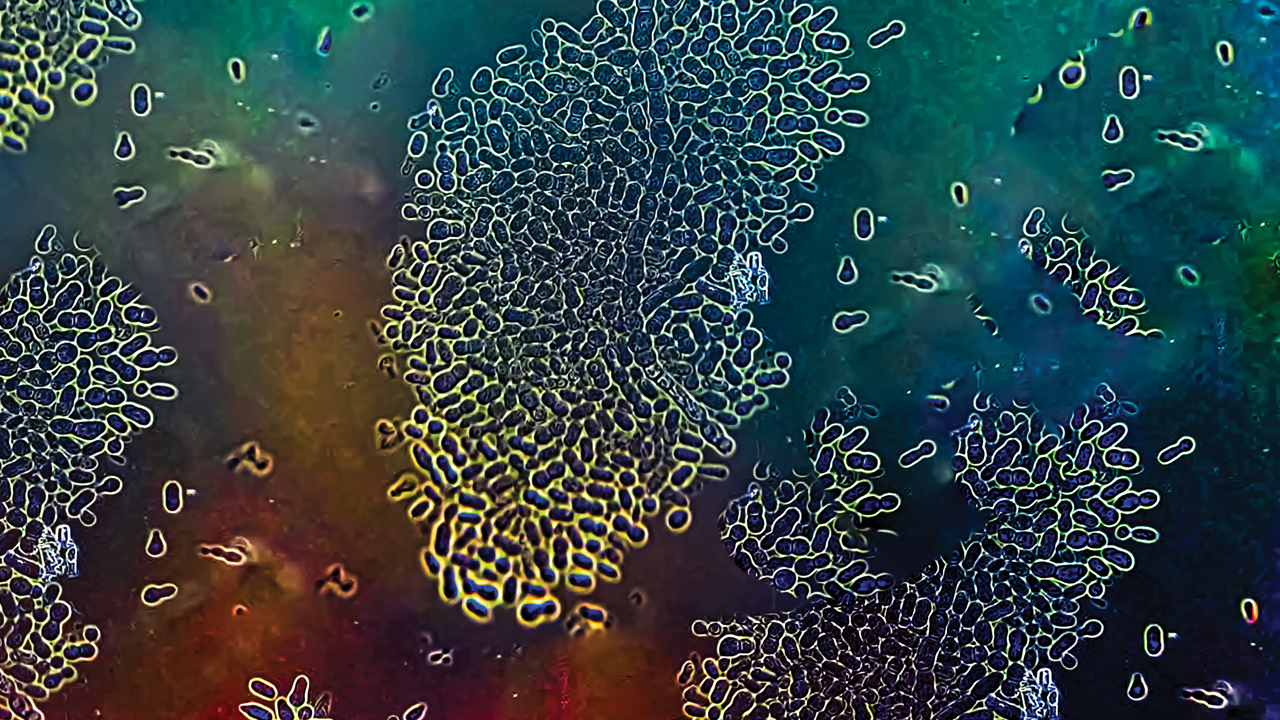

Everyone carries members of a group of fungi (the Malassezia) on their skin. Malassezia (pictured left) are yeasts, distant cousins to Saccharomyces cerevisiae used in baking and brewing, which thrive on fatty surfaces. “Sebaceous glands are thought to play a role in seborrheic dermatitis by creating a favourable environment for the growth of Malassezia,” Dr Ormerod says.

Malassezia colonises skin and releases enzymes (lipases and phospholipases) that break down fats in sebum. Malassezia uses the digested fats to grow. But the degraded fats, the yeast and enzymes, are irritants that can trigger inflammation in the skin, Dr Ormerod explains. The inflammation, in turn, weakens the skin barrier and causes erythema, itch and scaling. The weakened barrier also means that Malassezia and the inflammatory triggers penetrate more deeply into the skin.

Nevertheless, dermatologists still need to work out the details. “There is, for example, limited direct evidence that Malassezia causes seborrheic dermatitis. Studies have so far not demonstrated a higher density of Malassezia on the skin of patients with seborrheic dermatitis or any relationship between the amount of colonisation and severity of skin changes. However, the fact that most of the effective treatments for seborrheic dermatitis have antifungal activity gives indirect evidence of its role in the disease,” Dr Ormerod says.

Some dermatologists suggest that a particular type of virus (mycoviruses) may need to infect Malassezia before the yeast can cause seborrheic dermatitis. The virus may make Malassezia more likely to trigger inflammation. Changes in the populations of other skin microbes, such as the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, may also contribute. For example, some skin bacteria may break sebum down, which fuels Malassezia’s growth.

Androgens, such as testosterone, stimulate sebaceous glands to produce more sebum. While often described as ‘male hormones’, healthy women produce androgens. Indeed, in many, but not all studies, seborrheic dermatitis is more common in men than women. Often seborrheic dermatitis emerges for the first time around puberty. Such findings support suggestions that hormones contribute to some cases of seborrheic dermatitis.

Interestingly, people with acne are particularly likely to develop seborrheic dermatitis, but, people with atopic dermatitis (allergic eczema) seem less prone to seborrheic dermatitis. Dermatologists think that differences in the activity of the sebaceous glands, partly driven by hormones, may underlie these patterns of skin disease. Subtle differences in the immune system (seborrheic dermatitis is very common in people whose immune system is suppressed by disease or medicines), variations in sebum composition, high humidity and heat, as well as poorly understood genetic factors may also contribute to a person’s risk of developing seborrheic dermatitis.

Dr Ormerod adds that any reduction in the barrier function from any cause will increase skin reactions to external irritants and allergic triggers (allergens). So, masks, goggles and other protective equipment can exacerbate or trigger seborrheic dermatitis, by, for example, rubbing and over-hydrating skin, both of which can weaken the skin barrier. This explains why during the Covid-19 pandemic masks worsened or triggered seborrheic dermatitis in susceptible people.

Raising awareness

Education is the foundation of care for people with seborrheic dermatitis. You should remind patients and caregivers that seborrheic dermatitis is neither contagious nor caused by dirty skin. Stress and depression may trigger or exacerbate seborrheic dermatitis. So, advise people to take steps, such as mindfulness, yoga and walking in nature, to reduce stress. If you think a customer may be depressed, refer them to their GP.

A healthy diet may help to prevent symptoms of seborrheic dermatitis. A study in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology split 4,379 people into four groups based on the amount of fruit they ate. People who ate the most fruit were a quarter (24 per cent) less likely to develop seborrheic dermatitis than those who ate the least.

Several medicines, including commonly used drugs such as chlorpromazine, cimetidine, antipsychotics and hormonal treatments, can trigger or exacerbate seborrheic dermatitis. If seborrheic dermatitis emerges soon or markedly worsens after the patient starts or changes a medicine, speak to the pharmacist or refer the patient to their GP. Remind them to not change or stop taking any drug without speaking to their doctor first.

Managing symptoms

“If a child with nappy rash does not improve considerably after one to two weeks of topical treatment, then parents should consult their GP – their child may have something else. Nappy rash is worsened by friction, excessive moisture and irritation from urine and faeces in this area, so parents should consider managing these factors alongside treatment,” Dr Ormerod says. You can reassure parents that most children ‘grow out’ of cradle cap and nappy rash linked with seborrheic dermatitis by their first birthday. In the meantime, emollients can soften cradle cap. Barrier ointments can help treat and prevent nappy rash.

“Currently, there is no cure for seborrhoeic dermatitis and treatment aims to improve or clear the skin. There are some general tips to manage and prevent potential flare-ups. For example, patients can use gentle soap-free wash on their skin and areas affected by seborrheic dermatitis. After washing, a light moisturiser can help their skin barrier,” Dr Ormerod says. You could also suggest an over-the-counter emollient rather than soap or shaving cream.

Some cosmetics can trigger or exacerbate seborrheic dermatitis. “If the patient wears make-up, suggest that they pick products that do not block the pores, also called non-comedogenic,” Dr Ormerod adds.

“Information is key when it comes to managing inflammatory skin conditions and finding impartial advice can be difficult, in this internet age of misinformation. There is impartial, expert-written advice available that the pharmacy team can signpost patients towards. For example, the British Association of Dermatologists publishes online patient information leaflets for a wide range of conditions. They have QR codes for patients to scan and read on their phones,” Dr Ormerod says.

Seborrheic dermatitis, and skin diseases generally, are common among pharmacy customers. Remember that dermatological diseases are literally on show and unhealthy-appearing skin taps into deeply entranced biological systems to avoid parasites and other pathogens. So, skin conditions can affect a patient’s quality of life more than medically more serious ‘internal’ diseases. Nevertheless, the pharmacy team can do much to help patients and caregivers manage skin disease generally and seborrheic dermatitis particularly.

More information

- Download the British Association of Dermatologists patient leaflet at: skinhealthinfo.org.uk/condition/seborrhoeic-dermatitis/

- For more about managing nappy rash see: cks.nice.org.uk/topics/nappy-rash/.