In In-depth

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Anaphylaxis (a severe allergic reaction) often starts with a feeling that something just isn’t right. The patient’s throat and skin may itch, their airways may narrow – making breathing difficult – they may cough, feel that their heart is beating too fast or complain of light headedness.

Their stomach may cramp, they may feel nauseous, vomit or have diarrhoea. Their blood pressure may fall rapidly to dangerously low levels. They may slip into unconsciousness and, in some instances, die.

Looking at the stats

Adrenaline rapidly relieves anaphylaxis and can be a lifesaver, yet many people at risk of anaphylaxis do not carry or use their adrenaline auto-injector during an attack.

A 2018 US study published in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology found that only 44 per cent of adults and children always carried at least one adrenaline auto-injector.

Just 24 per cent carried multiple adrenaline auto-injectors: people often need a second dose to relive anaphylaxis. Some 45 per cent did not use adrenaline during a severe allergic reaction because an auto-injector was not available.

It’s similar on this side of the Atlantic. “There is a reluctance to carry and use injectable adrenaline and most studies of deaths due to anaphylaxis cite delay in treatment as a primary concern,” says Dr Shuaib Nasser, consultant allergist and respiratory physician, and the clinical lead for Allergy at Cambridge University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

“We continue to see persistent challenges within the community, with a large proportion of people with severe allergies, or their carers, not carrying or delaying use of an injectable adrenaline pen. This markedly increases the risk of negative outcomes and the need for additional emergency medical treatment,” adds Dr Helen Evans-Howells, GP and chairperson of the Anaphylaxis UK Clinical and Scientific Panel.

In July, however, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) approved adrenaline nasal spray (EURneffy) as an emergency treatment for anaphylaxis. Could this encourage more people at risk of anaphylaxis to carry and use adrenaline?

What is anaphylaxis?

The immune system seeks and destroys bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites, cancer and other threats to our health and wellbeing.

It also targets damaged tissue, which helps wounds heal and regulates inflammation, using antigens (immune triggers) to discriminate healthy tissues from foreign targets.

Essentially, allergies arise when the immune system over-reacts to a trigger that most people find relatively innocuous, such as pollen, peanuts or a bee sting. Anaphylaxis is a particularly severe allergic reaction.

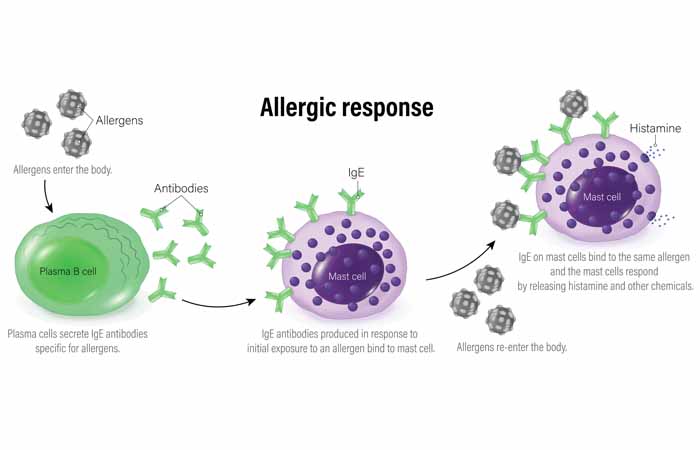

The allergen binds to antibodies (immunoglobin E; IgE) on mast cells and basophils, two types of white blood cell. The antibody is specific to a particular allergen. Typical causes of food-induced anaphylaxis in children include peanuts, hazelnuts, milk and eggs.

In adults, wheat, celery and shellfish are common triggers. Venom (e.g. wasps and bees) and medicines (e.g. antibiotics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)) can also trigger anaphylaxis.

Guidelines published by the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) note that several factors can make anaphylaxis worse or more likely including exercise, stress, infections, NSAIDs and alcohol.

What does it look like?

IgE’s binding to the allergen triggers the release of histamine and other chemicals (mediators) from mast cells and basophils. These drive inflammation, which is an important part of our immune defences. In some people, however, the ‘flood’ of mediators leads to the symptoms of anaphylaxis (Table 1).

The symptoms vary widely between patients. Nevertheless, the EAACI anaphylaxis guidelines note that skin and mucosal symptoms (e.g. mouth and throat) occur in more than 90 per cent of cases.

More than half of people experience respiratory and cardiovascular symptoms during anaphylaxis.

Typically, symptoms of anaphylaxis emerge within seconds to minutes of encountering the allergen. Sometimes, however, symptoms may develop two or more hours after exposure. Severe anaphylaxis tends to develop more rapidly than milder reactions. In up to about a quarter of cases, symptoms recur several hours later.

These ‘biphasic reactions’ may be particularly common with ingested, and so more slowly absorbed, allergens. The second phase tends to be less severe than the initial symptoms.

The patient, caregiver or bystander should call 999 if someone develops symptoms of anaphylaxis (Table 1). Meanwhile, the person should use their adrenaline auto-injector or EURneffy. Sometimes, a caregiver needs to administer adrenaline, so family and friends need to know what to do in an emergency.

The NHS suggests that the person should lie and raise their legs to help counter the low blood pressure. Pregnant women should lie on their left side. Raising the shoulders or sitting up slowly can help if breathing is difficult.

The NHS also suggests removing any sting from the skin and taking a second dose of adrenaline if symptoms do not improve after five minutes. People should not stand or walk, even if they feel better, and wait for emergency care.

How common is anaphylaxis?

Estimates of the prevalence depend partly on the criteria doctors follow to diagnose anaphylaxis. “The most commonly cited is that approximately one in 1,133 people in England experience anaphylaxis at some point in their lives,” Dr Nasser says.

Fatal, and often avoidable, deaths from severe allergic reactions capture headlines. People may die from the attack itself, brain damage caused by anaphylaxis or issues related to resuscitation.

Thankfully, deaths from anaphylaxis are rare: there are about 20-40 a year according to the UK Fatal Anaphylaxis Registry.

In general, deaths from anaphylaxis become more common as patients age, possibly because older people are less able to cope with the effects of anaphylaxis.

Diagnosis is important to ensure those that need adrenaline receive the device that’s right for them, identify the triggers and to see if other treatments could help.

Immunotherapy (desensitisation), for example, ‘trains’ the immune system to tolerate certain allergens. However, obtaining a diagnosis and immunotherapy can be challenging.

“There is a lack of allergists in the UK with long waiting lists and demand greatly outstripping supply and very few doctors are being trained as allergists. Some parts of the UK, such as Scotland, have almost no full-time allergists,” Dr Nasser says.

What is EURneffy?

Pharmacologists divide the nervous system outside the brain and spinal cord into enteric (gut); parasympathetic; and sympathetic.

Adrenaline, a hormone released from the adrenal glands on top of the kidneys, stimulates the sympathetic nervous system.

In people with anaphylaxis, injectable or nasal adrenaline increases heart rate and force, raises blood pressure and opens the airways.

Adrenaline also alleviates, for instance, itch, rash, angioedema (swelling caused by fluid leaking from blood vessels) and gastrointestinal (e.g. diarrhoea) symptoms.

In July, the MHRA approved EURneffy as an emergency treatment for anaphylaxis.

“Patient safety is our top priority, which is why we’re pleased to approve the first needle-free nasal spray formulation of adrenaline for the emergency treatment of anaphylaxis in the UK. Until now, adrenaline for self-administration has only been available via auto-injectors,” says Julian Beach, MHRA interim executive director of Healthcare Quality and Access.

"While this represents an important new option, adrenaline auto-injectors remain a vital and potentially life-saving treatment, giving people experiencing anaphylaxis valuable time before emergency help arrives.”

EURneffy is a ready-to-use nasal spray that delivers a single dose of 2mg adrenaline when activated. It alleviates anaphylaxis as quickly as adrenaline auto-injectors, even when the nose is congested from a cold or allergy.

“A nasal adrenaline spray addresses several critical barriers seen with the current standard of care, such as portability, fear, hesitancy to act and incorrect administration,” Dr Evans-Howells says.

“With this option… we hope and expect to see an increase in the number of patients and carers who both carry and confidently administer adrenaline promptly when needed.”

The most common side-effects after a second 2mg dose (4mg total) dose of EURneffy in clinical studies were: throat irritation (18.8 per cent); headache (17.6 per cent); nasal discomfort (12.9 per cent); and feeling jittery (10.6 per cent).

No serious adverse drug reactions emerged during the clinical studies. The MHRA approved EURneffy for adults and children weighing at least 30kg.

Future developments

Anaphylaxis UK notes that a 1mg dose of EURneffy, suitable for children weighing 15-30kg, is approved in the USA and under review by the European authorities. The charity suggests that the 1mg dose could be launched in the UK in 2026. In the meantime, certain children will still need injections.

Furthermore, some people will prefer injections, if, for example, they want the reassurance of a familiar treatment. “Most other people are likely to prefer nasal administration,” Dr Nasser says. Indeed, he predicts that over time, nasal adrenaline is likely to become the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis “due to its ease of carriage and administration”.

Anaphylaxis is frightening for patients, families and onlookers. People at risk of anaphylaxis should carry at least two adrenaline devices, ensure patients, friends, family or caregivers know what to do in an emergency and, of course, read the labels or ask about allergens.

Deaths may be rare, but prompt treatment further reduces the risk, which makes EURneffy an important advancement.