In In-depth

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

You could be forgiven for thinking that syphilis is little more than a scourge in period dramas, an aside in history documentaries or a footnote in Shakespearean plays. But syphilis is making a comeback. In 2022, infectious syphilis diagnoses reached the largest annual number since 1948. “Fifteen years ago congenital syphilis, where syphilis is acquired while in the womb, was very rare. It’s still uncommon,” adds professor Matt Phillips, consultant in genitourinary medicine and HIV in North Cumbria and president of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH). “But the fact that we still have cases of congenital syphilis in the UK in the 21st century should be a wake-up call.”

So, how can the pharmacy team help?

The stages of syphilis

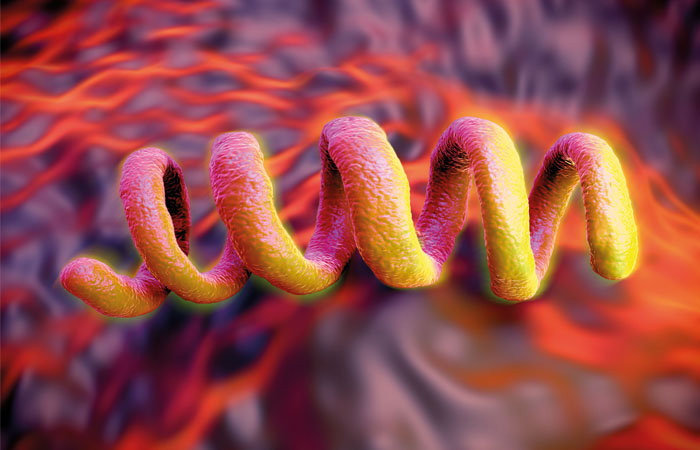

Broadly, syphilis (previously sometimes called the pox) develops in three stages. Most people catch Treponema pallidum, the spiral-shaped (spirochaete) bacterium that causes syphilis during vaginal, anal or oral sex with a person with active syphilis. According to guidelines published by BASHH, about a third of sexual encounters with an infected person result in the partner developing syphilis. Some studies suggest the rate is as high as three in every five.

Syphilis also spreads non-sexually. People who inject drugs can catch syphilis from needles and other contaminated drug paraphernalia. In theory, blood transfusions can carry the infection, so the UK screens donated blood for the bacterium that causes syphilis.

“Good sexual health is a backbone of healthcare”

About three weeks after infection, although this can vary from nine to 90 days, most people with syphilis develop a round and painless ulcer (a chancre) at the point of sexual contact, which may be the penis, labia, cervix, around the anus or mouth. Chancres discharge clear fluid, rather than pus, and are not usually painful. Some people may develop several chancres, but this is rare. These ulcers usually disappear after two to eight weeks. At this stage, people may not realise they have syphilis.

About a quarter of patients who do not receive penicillin when they have a chancre develop secondary syphilis. This stage usually emerges between four and 10 weeks after the chancre’s appearance. People with secondary syphilis may experience, for example, fever, fatigue, weight loss, sore throat, patchy hair loss, swollen lymph nodes, recurrent ulcers in the mouth or genitals, or a skin rash. The rash can occur anywhere, but particularly affects the palms and feet. These symptoms mimic many other diseases. Indeed, doctors call syphilis “the great imitator” so, it is especially important to remain vigilant for possible syphilis symptoms.

The secondary symptoms usually last about three to 12 weeks. But by now, the syphilis bacterium has spread throughout the body. After the secondary symptoms resolve, about two in every five patients enter the latent stage. During the latent stage, which can last 10-40 years, the patient does not experience symptoms and cannot pass syphilis to other people.

Some people, however, relapse into secondary syphilis. Others develop tertiary syphilis, where the bacterium invades the brain, eyes, heart, nerves, liver, bones, joints and other organs. “We are not seeing a marked increase in tertiary syphilis, possibly because people receive antibiotics for other reasons,” says professor Phillips. Untreated tertiary syphilis can, however, be fatal.

“Infectious syphilis diagnoses had increased by 15.2 per cent since 2021”

Increasingly common

During the 1920s, syphilis killed about 60,000 people a year in England and Wales. Penicillin means that we’re nowhere near those levels. Nevertheless, in 2022 the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) reported that infectious syphilis diagnoses had increased by 15.2 per cent since 2021 to 8,692 – the largest annual number since 1948. “The reasons underlying the rise in the number of syphilis cases are not clear. In part, the risk seems to reflect an increase in testing and a growing awareness of the symptoms to watch for. So, more people are being tested and treated, which is great,” says professor Phillips.

Increased awareness and treatment do not, however, tell the whole story. “We don’t fully understand how Covid-19 affected sexual behaviours that may have contributed to the rise,” says professor Phillips. During 2022, doctors diagnosed 82,592 cases of gonorrhoea, an increase of 50.3 per cent compared with 2021 and the highest number in any year since records began in 1918. The rise in gonorrhoea supports suggestions that sexual behaviour may have changed since the pandemic.

“Men who have sex with men [MSM] are at most risk, but anyone can get syphilis,” professor Phillips warns. In 2021, 71 per cent of infectious syphilis diagnoses were in gay, bisexual and other MSM. So, more than a third were in heterosexual and other groups. The rate is highest among people of black Caribbean backgrounds. “There is plenty of evidence suggesting we must work harder to meet the needs of people of black Caribbean background and syphilis is yet another reminder of that,” says professor Phillips.

HIV and syphilis share risk factors, such as unprotected sex and sharing drug injecting equipment contaminated with blood. According to the BASHH guidelines, about two in every five white MSM aged between 25-34 years with syphilis also has HIV. But the relationship seems more intimate than just shared risk factors.

The BASHH guidelines note, for example, that people with HIV may develop a greater number of chancres that invade more deeply into the underlying flesh. In people with HIV, the chancres may persist as the patient enters the second stage. “We don’t fully understand the relationship between HIV and syphilis. We don’t know whether the infections change the patient’s susceptibility or whether the pathogens interact in some way. A direct interaction between HIV and syphilis seems possible, but we don’t really know,” professor Phillips says.

Despite prenatal testing, congenital syphilis seems increasingly common. About 15 per cent of children will be infected if the mother caught syphilis more than a year before her pregnancy. The risk that the child will have syphilis rises to between 50-70 per cent if the mother has early syphilis during pregnancy. So, the NHS screens pregnant women for HIV, hepatitis B and syphilis.

In 2018-2019, the latest Government data available showed that 1,022 pregnant women in England screened positive for syphilis. Almost a third of these were newly diagnosed and needed treatment. The fact that every eight hours a pregnant woman screens positive for syphilis further highlights the importance of early detection and rapid treatment.

‘Think syphilis’

For several years, BASHH has highlighted the long-term underfunding of sexual health services (SHS) in the UK. In England, the NHS does not fund SHS. Central Government allocates funds for SHS as part of the public health budget to local authorities. “Funding for SHS did not increase during the outbreak of mpox [previously called monkeypox] and we haven’t caught up. Of course, all public services face a general financial squeeze. But SHS urgently need more funds. Apart from the rise in syphilis, gonorrhoea is increasingly common and we don’t have the resources, and we have dwindling expertise, to do robust contact tracing. We are also seeing rising need to access abortions, which is linked to poorer access to appropriate and acceptable contraception,” professor Phillips notes.

Pharmacy teams can, however, help reduce the spread of syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) by reminding people of the UKHSA’s recommendation that “everyone having sex with new or casual partners [should] wear a condom and get tested regularly, whatever their age or sexual orientation”. The UKHSA suggests that gay, bisexual and other MSM should be tested for HIV and STIs annually or every three months if they do not use a condom when having sex with new or casual partners.

“Pharmacists and their teams need to keep syphilis and other STIs in mind when they see certain patients. Pharmacy teams should refer people who experience several episodes of thrush and men who report a burning sensation when they pass urine to the local SHS or GP. Pharmacists can refer people to SHS directly, without the patient seeing a GP,” professor Phillips adds.

“Better patient education is needed to inform people about the symptoms, not just in higher risk groups but also in the general population. GPs and practice nurses also need education so that they ‘think syphilis’,” he concludes. “Good sexual health is a backbone of healthcare. Pharmacists and their teams are in the forefront of healthcare in their communities. They may see people with STIs before the GP and can help prevent the continuing rise in the number of cases of syphilis and other STIs.”