In Conditions

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Most people will have experienced a headache at some time in their lives and self-managed the pain with analgesics. However, many patients will seek advice from community pharmacies, especially if the headache persists for more than a few days. A headache is a symptom, rather than a disease, with many different causes. Pharmacy staff therefore need to be aware of the key symptoms associated with the more common causes of headaches to decide whether it can be managed within the pharmacy or if onward referral is needed.

The British Association for the study of Headaches (BASH) have grouped headaches into two categories; primary and secondary. Primary headaches are the most common type, accounting for nearly 98 per cent of all cases. Secondary headaches occur as a consequence of another condition. The more common primary headaches can be managed in community pharmacies as discussed below.

Primary headaches

Tension-type headaches (TTH)

This is the most common type of primary headache, affecting between 30-80 per cent of the population. A TTH can be infrequent, frequent or chronic. Infrequent TTHs occur less than once per month, whereas patients with a frequent TTH experience at least 10 episodes on fewer than 15 days per month. Finally, a TTH is considered as being chronic when someone has more than 15 episodes in a month.

Typical symptoms

Patients experience a dull ache or pain which remains at the same level of intensity, i.e., it doesn’t really get any worse. Usually, the headache is described as:

- A band of mild to moderate pain across the forehead

- A sensation of pressure or tightness e.g., like having a tight band around the head.

A TTH develops gradually, with a general worsening of the pain throughout the day. It can persist for anywhere from half an hour to several days. Although uncomfortable, a TTH rarely affects someone’s ability to sleep and people can continue to work.

The main causes of a TTH include:

- Stress/anxiety or lack of sleep

- Eye strain

- Hunger

- Exposure to bright sunlight, heat/cold or noise

- Alcohol/caffeine or even dehydration.

Managing tension-type headaches

A TTH is not serious and will always resolve over time. An infrequent TTH responds to simple analgesics e.g., paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen or aspirin. Patients with frequent or chronic TTHs should be referred to their GP. Paracetamol is suitable for a pregnant woman although both paracetamol and a NSAID can be used during breast-feeding.

If the above measures fail, combination products containing caffeine can be used. Caffeine itself is not effective but does appear to be beneficial in combination paracetamol, aspirin, or ibuprofen. Codeine is best avoided because it is associated with a greater risk of medication-overuse headaches (see opposite page). Where combination therapy fails patients should be referred to their GP.

“Patients describe the pain as severe and burning-like, as if they have a hot poker in the eye”

Is it a brain tumour?

Patients whose headache lasts for a few days may worry that it is caused by a brain tumour. But, according to Dr Nicholas Silver, consultant neurologist at the Walton Centre and Trustee at OUCH UK, “patients presenting with brain tumour will normally not present with isolated headache, but they will have additional neurological problems, most commonly seizures or focal neurological symptoms and signs”. Dr Silver did suggest, however, that staff should look out for symptoms suggestive of a raised intracranial pressure such as a “headache specifically induced by cough, sneeze, or strain and transient seconds of complete blacking of vision in one eye on standing”. He added that those with raised intracranial pressure “will prefer to be sitting or standing and headaches will be worse on waking, i.e., before getting up or moving”.

Cluster headaches

Cluster headaches are the most common form of primary headache type known as trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia. Fortunately, cluster headaches are rare but represent one of the most severe primary headaches. A cluster headache will always only affect one side of the head (although the side might change with recurrent bouts). The pain itself is usually centred around or behind the eye, temple or forehead. Patients describe the pain as severe and burning-like, as if they have a hot poker in the eye.

Associated symptoms, as well as searing eye pain, can include:

- Eyelid oedema together with redness

- Lacrimation

- Nasal congestion/rhinorrhoea

- Agitation.

The headache attack arises over a period of about 10 minutes and can last anywhere from 15-180 minutes and occur at any time of day or night. Typically, patients experience attacks of pain with a frequency of between once and up to eight times a day. These headaches occur in clusters and can last for six to 12 weeks at a time.

Management

Patients with symptoms of a cluster headache should be promptly referred to their GP for assessment and treatment.

“There is little evidence to support the use of opioids in acute migraine”

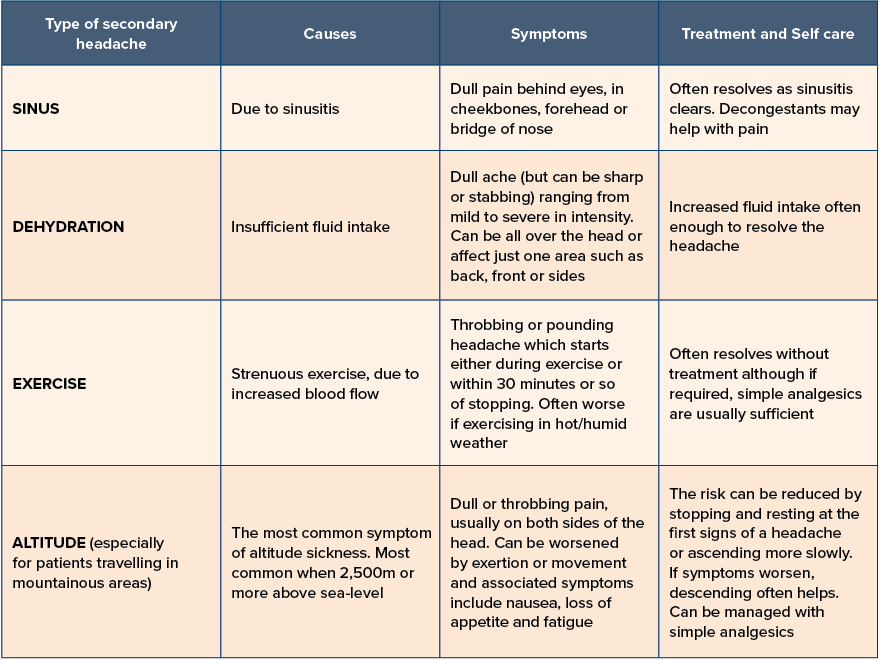

Secondary headaches

Although secondary headaches are much less common and are often a cause for concern, there are actually several types of secondary headaches which can be encountered in pharmacies that arise from an easily treatable cause, as shown in the table above.

Medication over-use headache (MOH)

A headache that is present on at least 15 or more days per month among those with a pre-existing primary headache disorder is referred to as a medication over-use headache (MOH). Such headaches develop following the regular use of one or more drugs (in particular codeine-based analgesics or triptans) for acute headaches over a period of three months or longer. It is common among patients with migraine but can occur in those with a TTH. Complete withdrawal of all analgesics is recommended, although headaches tend to worsen for the first one to two weeks. In addition, patients may experience nausea, vomiting, reduced appetite, tachycardia, sleep disturbance, anxiety, and restlessness.

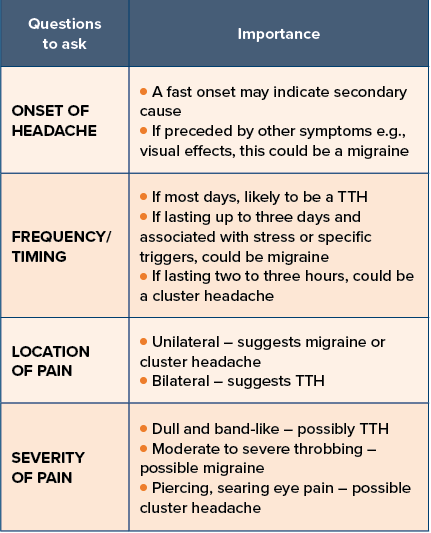

Assessing a patient with a headache

It is often helpful to ask the specific questions outlined in the table below to help establish the most likely cause.

Migraine headaches

Episodic migraine is the most debilitating primary headache, affecting around two per cent of the general population. Migraine can be further divided into two sub-types:

- Migraine without aura

- Migraine with aura (sometimes referred to as classic migraine).

Migraines are described as episodic, when the headaches occur for less than 15 days a month, or chronic (more than 15 episodes per month) and present for over three months. Interestingly, between 20-60 per cent of migraine sufferers have what’s termed an intuitive or prodromal phase, sometimes up to 24-48 hours before the onset of symptoms.

The diagnosis of a migraine is made using the following criteria:

Diagnosis of migraine without aura

- A headache lasting four to 72 hours if untreated.

AND at least TWO of the following:

- Unilateral pain (although in 30-40 per cent of cases the headache is bilateral)

- Pulsating or throbbing pain

- The pain is of moderate to severe intensity

- The pain is worsened by physical activity such as walking/climbing stairs.

AND at least ONE of:

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Photophobia (sensitivity to light) or phonophobia (sensitivity to sound).

Diagnosis of migraine with aura

Around a third of patients experience an aura with their migraine. The diagnostic criteria for migraine AND at least two attacks in which ONE or more of the following temporary symptoms:

- Visual changes – e.g., seeing a zig-zag pattern which is often described as looking like the walls of a medieval castle

- Unilateral numbness – affecting one hand or one side of the face

- Speech or language problems – known as ‘transient aphasia’ so that when patients speak or write what comes out is often unintelligible.

Auras can lead to a partial loss of vision and occur 10-30 minutes before the onset of the headache itself.

Although the criteria above is needed to make a formal diagnosis of migraine, Kate Sanger from the Migraine Trust suggests that “asking three simple questions can help diagnose if a patient has migraine”. These she says are “asking if their headache over the last three months has been accompanied by sickness or nausea, interfered with daily activities and if they have also experienced an increase in sensitivity to light”.

Triggers

Common causes of migraine include stress (most common), disturbed sleep, irregular eating or skipping meals, excessive intake of caffeine intake, a lack of exercise, strong odours and in women, menstruation.

Treatment of acute migraines

Simple analgesics at the start of a migraine are often enough to control the pain in most cases. Ibuprofen 400mg, aspirin 900mg and paracetamol 1000mg (suitable for women who are pregnant) are good options.

Buccal prochlorperazine 3mg can be taken for any associated nausea or vomiting. Another commonly used over-the-counter (OTC) treatment contains paracetamol and codeine and/or buclizine, which helps to settle any nausea. However, there is little evidence to support the use of opioids in acute migraine.

If the above treatments are not effective, then sumatriptan 50-100mg tablets can be tried either alone or together with either paracetamol or NSAIDs. If a patient says that they experience a migraine with aura, then the sumatriptan should be taken not at the onset of the aura, but once the headache starts.

For both pregnant and breastfeeding women, paracetamol is the preferred first-line treatment for acute episodes and sumatriptan is not licensed for OTC use. Aspirin and opiates should be avoided in pregnancy.

Preventative treatment for those with more frequent migraines or where acute therapies are ineffective are available on prescription, e.g., propranolol, topiramate and low dose amitriptyline.

Red flags

Important red flags with any headache include:

- A sudden onset headache that becomes worse within five minutes, also known as a thunderclap headache

- Associated neurological problems e.g., limp or facial muscle weakness or numbness

- Associated systemic upset e.g., general malaise, fever, fatigue

- Headaches in patients aged over 50 as this is an independent risk factor for an intracranial problem.